“The Painting” is a short film, created in response to work by the artist Nicola Durvasula. It will form a part of her new exhibition, PANG, at Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke in New Delhi, India, from March 22 until May 17, 2025. Whether the Voiceover represents one arguing consciousness or two, or none, is a matter for the viewer to decide.

Narration: Will Eaves. Painting: Nicola Durvasula.

Carillon – for organ

This is a Sibelius digital file of a piece written in 1991 (and revised in 2023) for the Marstal Church Organ, built by Frobenius & Sons, on the island of Ærø in Denmark. As Kate Bush once said of The Dreaming, play it loud. The score will be published in The Point of Distraction (TLS Books) later this year together with a suite for piano (Four Diptychs), played by Richard Uttley.

What is ability?

1.

We think of ourselves as creatures with willpower and rights of self-assertion, but it is surprisingly hard to think for oneself.

Original thought always involves non-compliance with precedent, and in a systematic society and economy that is tricky, both practically, because it is for example hard to run one’s life offline, without the various permissions of web-based administration, and emotionally, because it’s a way of saying no to authority. Refusing the known produces feelings of uncertainty, the possibility of disappointing others or being disappointed by them. It’s an old problem to do with hierarchy and the individual. Explicit examples, in narrative literature, are Abrahamic myth, The Tempest, and 1984. But even Pride and Prejudice and Persuasion qualify. Austen’s novels are not about romantic love; they are stories about the practical and emotional obstacles in the path of truth-seeking, and the way families and riches do not take kindly to daughters who disappoint them.

Creative ability is always a move beyond, or rather into, uncertainty and the fear of unforeseeable consequences. It’s always an act of refusal or of resistance to something already established, even if you are adding to it. Extension is an outward trajectory; it involves a move away from security. In logic and mathematics, it involves accepting the profound consequences of inconsistency and incompleteness, the true propositions that cannot be proved from the axioms; in art, it requires the painstaking undermining of preconceptions, including the idea that writing a book or a poem is about deciding to write a book or a poem rather than discovering the form as you go. Scientific method and artistic construction are both matters of formal experiment and experimenting with form. (It still amazes me how few scientists and artists point this out.)

Ability is also resistance to oneself, what one has already done, one’s effortful CV, one’s “skills”, the carefully curated evidence of a thing called identity, as if identity were a set of emotional and behavioural cues on a plinth in a museum, or indeed a university staff card. It’s in this sense of extension and resistance that I understand George Orwell when he says, in his 1946 essay, Why I Write, that literature is driven both by powerful personal motives, “ingrained likes and dislikes”, and by the constant struggle “to efface the personality” in pursuit of the truth.

What, then, is the “ingrained” component of ability? In her excellently clear book, Heart and Mind (1981), the philosopher Mary Midgley makes a case for the existence of innate gifts, not as quantities of intelligence feeding entitlement or its opposite, but as “personal repertoires” of “tastes and powers which can often startle both ourselves and those around us, which may find no path in our culture”. Her defence of the personal repertoire perhaps relies too heavily on unprecedented geniuses like the Indian mathematician Ramanujan, who had very little education. You can’t infer a general truth about innate ability from such examples. We are not commonly exceptional. Yes, of course, we are different; but by degree, I suggest. If that were not so, we would be condemned to lead solipsistic lives, and others’ abilities would be inappreciably mysterious to us.

I also think that innatism by itself is not enough to explain our changes in life, our adoption of trades, practices and activities that run counter to an apparent inheritance. This is more than adaptability; it’s the will to change ourselves and the world by refusing something given. We may have a predisposition to draw or paint or calculate and yet object to doing so on emotional grounds (our parents did it!). What we later find, typically, is that the draughtsman’s gift is re-expressed in another direction, mathematically or musically or paleontologically. As a species, we have learnt to do many things. Most animals do the same thing, but we specialise within the group, and even as we specialise we diversify: there are many tasks to be done and we can learn to do each other’s tasks, up to a point (though always get a good plumber). What this doesn’t alter is the idea of an underlying subjective disposition – including the ability to have a go at various things in accordance with our temperament or in defiance of it.

Midgley is quiet about this second possibility. She discusses abilities rather as if they were unique-to-user applications, whereas I see them as conscious variables inclining, over time, to expressions of personality. This takes us away from innatism or biological programming to something more intriguing: the ability to educate ourselves, building not just on clear aptitude – the thing that comes naturally – but on what we can’t do so easily, but might, with the right teacher, find interesting.

The word “education” has two Latin roots: educare, which means to train, and educere, to lead or draw out. The second of these is the one that tends to be forgotten. Drawing out presupposes the ingrained or innate; it also suggests the hidden, submerged, and contrary. We’re not just drawing out an obvious talent. Thwarting ourselves, steering away from what comes easily, is often at the heart of a breakthrough. The tussle is itself the expression of something. In this sense, the gift of an ability is difficult to pin down. It’s often counter-intuitive, a kind of Turing-esque or Gödelian problem, in which unprovable truths are at the heart of defined processes, in which it is simultaneously true that I can write novels and that I dread so doing, or that my attempts to avoid writing are themselves a kind of preparatory activity. Keats famously called this state of resistance Negative Capability, “that is, when a man is capable [my italics] of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact or reason”. Orwell is all irritable reaching by comparison, but his relationship with a talent that expresses itself uncertainly as the inverse of ability – debility, indeed – is one Keats would have recognised. “Writing a book”, he says, “is like having a long, horrible illness.”

2.

Ability is both innate and shaped, determined and acquired, but it is in all cases the property of a conscious entity. That education appears now to be mandating acquisition of something off a menu called “skill” over any real feeling for the experiential uncertainties of art, music, language, or indeed scientific method, is something that should concern us. The concomitant problem is not so much that machines will acquire conscious abilities, but that we are already some way along the road to forfeiting ours.

It is possible, just, to say no to systems like exams and SATS and phone upgrades and the tiers of administration in workplaces, but they are now firmly, normatively embedded in our lives, and by and large we do not stop to question them. We don’t feel that we can. Technological systems owned by private corporations (in California, mostly) are essentially dominance hierarchies, like religions, or powerful families, and like those other institutions they greatly elevate the notion of control as a force for good. We are leading better lives by compliance, they say. We are in control by allowing ourselves to be controlled. We need this upgrade. Everything is easier if we just say yes. In such a long-lived protocol of submissiveness – Julius Caesar, Elizabeth I and Stalin would all have recognised its utility – requests from an almost numinous electrical authority are to be understood as commands, and no command in practice may be refused. If you don’t say yes, there will be consequences. You will be locked out of your bank account, you will not be able to order your medication, you will not get onto your degree course or be able to graduate. Notice in all cases, that the content of the account, the nature of the need, and the substance of your work and argument, your ability, are utterly irrelevant. It is simply non-compliance that signifies. Notice, too, that whoever is at the head of the hierarchy is usually exempt from these consequences.

In his Gifford lecture on “The Religious Experience”, the sceptical cosmologist Carl Sagan has this to say about codes of submission: “Consider how we bow our heads in prayer, making a gesture that can be found in many other animals as they defer to the alpha male [. . .] We’re enjoined in the Bible not to look God in the face, or else we will die instantly. In the court of Louis XIV, as the king passed, he was preceded by courtiers crying ‘Avertez les yeux! Avert the eyes. Don’t look up.’” I confess I’ve thought much the same as Sagan in various seminars, when no one looks up, or when I’m walking down the street, and I see students, everyone, myself included, bowing to the phone light.

It takes about three years to get the fear of God out of my students. To help them to see that getting a few low marks doesn’t matter, that the fear of losing their place in the hierarchy of grades is an anxiety about power and influence deliberately fostered by one model of economics among many, that they are more than their earning capacity, and that the point of literature, as Auden said in his introduction to Poems of Freedom, is not to make us more efficient, but to make us more aware of ourselves.

The technological climate, in which capacity and influence are so important, has confused freedom to develop the person you already are with the acquisition of power and status. Students want jobs; I hope they get them. They have loans to repay. But they also want to be successful; they tell me in their essays that they know they’re smart, but that they’re struggling to see the point of a second-class degree; and I worry that this generation, more than any other, sees recognised achievement – success granted by an authority, often an absent and quasi-religious electronic one – as the goal of learning. That is what they are being told, after all. That is what Nicky Morgan, the former Secretary of State for Education, meant when she said that studying the arts holds pupils back. (Never mind that the creative industries are worth more than £80 billion a year to the UK economy. Never mind that the whole Renaissance humanist project – without which no rationalism, no economics, no Bacon, no Newton – was enshrined by the study of grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry and philosophy.) She meant that there is no development without competition and, it is implied, reward.

It is the materialist-individualist creed, of course, and like every iteration of that delusion in every age, it never asks, simply and logically, what individuals will do with their reward, and how they expect it to shelter them from misfortune or make them happy – what relationship it has, finally, to the conscious inner life.

This is the point. Human ability is conscious and therefore intentional: it grasps meaning and has a felt, as well as reasoned, relation to the world in which it operates. It values what is being done as it is done: look at a toddler clapping its hands when one brick stays on top of another. It is not merely attributed or assigned relative to an observer, like a message “sent” by Outlook; it is experienced, and experienced both by the persons with the ability and the people around them. It is the fact that we experience a great singer for ourselves that makes his or her ability so moving. If it were merely a matter of manifesting technique, there would be no need to involve a conscious audience. But in practice, and in all cases, ability, whether we choose to do anything with ours or not, is potentially communicative and reflective as well as personal: in someone else’s unique gifts – let us at last call it their sensibility – we experience the emotional echo, and the limit, of our own, and that sense of frustrating limit is important in defining who we are. “We are looking for freedom, not omnipotence,” Midgeley reminds us, and freedom – the ability to be ourselves – has mortal limits. “Real gifts, in their nature, are limited.”

A talk first given on September 25, 2020 at CODEX: Leonardo at 500, Royal Society, and first published in Broken Consort (CB Editions), 2020.

Ariel in Texas

A devil, an eddy, an air ambulance:

I wish I were any of these things

and not the sort to raze where I have been.

Last night? Where was I last night?

Turning the bridge into a whisked piano,

making killer passes at cattle. The limit

What would I not give to put things back,

spin blindfolds out of thunderheads.

No one, then, would look on my lowing

except as necessary grief, the wind

in wrangled spars astride the Brazos

and the buzz of telegraph wires.

First published in Sound Houses, Carcanet, 2011.

The Absent Therapist

Some pieces of work are never finished. In 2014 I put together a serio-comic book of voices, The Absent Therapist, which at different times I’ve tried calling “an experimental novel”, a “group of miniatures”, and a “collection of prose”. It was always fiction, but not necessarily (or exclusively) fiction for the page. Since that first publication by CB Editions, Therapist has been a teaching-aid, a cabaret, and a live edition, with Prof. Sophie Scott, of the science-literature podcast The Neuromantics. Now it’s a one-off audio drama, engineered by Mark Lingwood and Bibi Berki of Tempest Productions, with some piano music. You can listen to it, for free, on Soundcloud and Spotify or your platform of choice; or listen/download here:

https://www.tempestproductions.net/podcasts/episode/90f8e028/the-absent-therapist

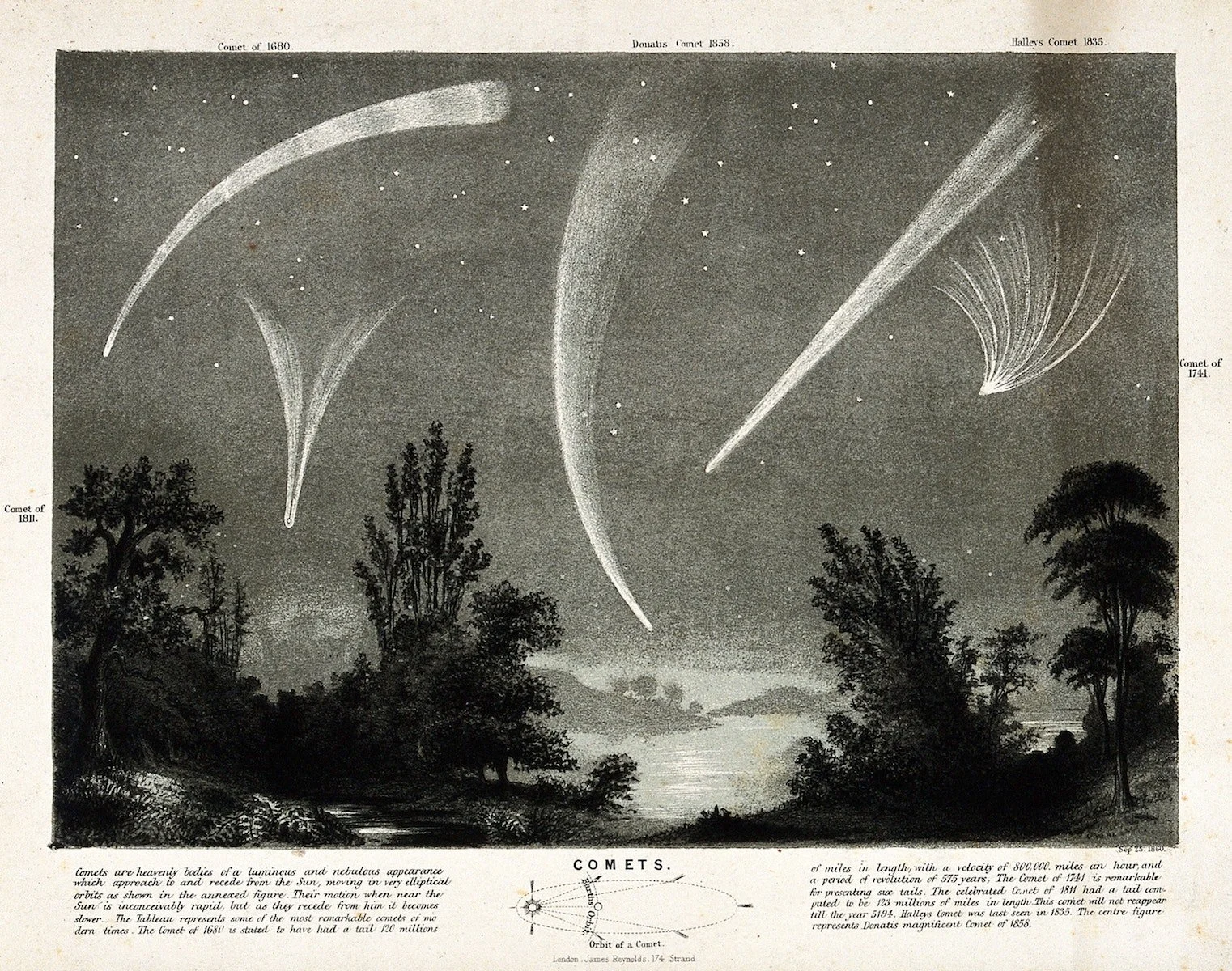

An 1860 engraving, representing Halley's Comet (1835), Donati’s Comet (1858), and others

Journal of the Plague Year

Like a comet, its time has come again. Frantic and austere, the feeling for personal bewilderment running fast beneath the author’s plain style, Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year (1722) brims with recognisable situations – the wealthy thundering down the road to Oxford and safety, the poor condemned by the riskiest essential employments (searching, guarding, nursing, burying), the revelation of powerlessness in authority, the joy of deliverance, and the shortness of memory. It’s tremendous in every respect, as an invention sprung from fact, as a dramatic monologue, as a composition disordered by its own subject-matter. To offset its evil charms, I’ve tried reading it alongside Gustave Flaubert’s L’Éducation Sentimentale (1869) – as different a novel as one can imagine – only to find strange resonances. In both books the act of fascinated witness has a sort of immunising property, and Frédéric Moreau wandering the streets of the 1848 insurrection in Paris is uncannily similar to HF, Defoe’s narrator, making his way past plague victims screaming at their casements in London in 1665. In each description of chaos and disaster, the past tense is full of threat, because the past is where we’re all headed. I imagine scenarios for a film version of Journal and then watch the evening news: like Defoe, I’m inventing things that have already happened.

It would make a terrific, if unusual, film. The novel is a quasi-documentary of the last great visitation in this country, and it draws on a variety of reportorial (and sermonising) sources, including London’s Dreadful Visitation (1665), which supplied the statistics and bills of mortality, and Thomas Vincent’s God’s Terrible Voice in the City (1667), as well as a not-too-remote historical memory of the capital as it was when Defoe was a young child – London in all its working vitality and stupid luxury in the middle of the gay restoration. Producers would want to know: whose story is this? But that is the wrong question to ask. They tend to confuse narrative fluency with heroism, and the two have no necessary relation to each other. Main characters are a secondary consideration when your main character is an epidemic. Protagonists are swept away, and Defoe drives the point home: “It is not the stoutest courage that will support men in such cases.” The disaster tops the bill, so to speak, and like a villain or avenging angel, it doesn’t look so bad at first, beginning in Long Acre in December 1664, appearing sporadically, but confined to St Giles, Cripplegate and adjacent parishes, until early summer, then breaking out and surging east across the city and the suburbs before raging south and north, and onwards, with the remnants of trade and waves of refugees, to other cities in August and September, when thirty thousand died in three weeks alone.

Look at the YouTube posts of the Boxing Day tsunami of 2004. The wave is a trickle of water, an uninterpretable swell, until we see it up close at the last minute, smashing boats and houses with a kind of lazy insistence. In the same way, the key to getting a screen adaptation right would be to reproduce the novel’s air of delayed or haphazard suggestion, the filtered awareness of what’s really happening at which humans and governments, alike frightened for their survival, excel. No period bile, no endless suppuration, no Matthew McConaughey and his blinding teeth (again, not usefully heroic: rotten “teeth” killed 946 people in August and September, says Defoe). Much better to have people disappear in the night, as they do, and did; for the red cross to appear on the door and go unremarked. By day, people carry on, at least for a while: this is the British reserve in full muffled cry, and a proof of our natural tendency to exceptionalism. In one grimly funny scene, Defoe has a citizen boasting about the good health of his drinking companions, “upon which his neighbour said no more, being unwilling to surprise him”. (Defoe is not, as a friend put it, the most “huggable” of novelists.) Have the mayhem in long shot or parenthesis – the man who runs mad and naked into the Thames while others conduct business on the foreshore, the dead cart running down Aldgate with the driver in his seat but the reins fallen from his hands, a shop opening while the house next door is boarded up. Get it wrong, cast for charisma, and you end up with a seventeenth-century zombie movie, where survival becomes heroic, and we are once more at the predictable mercy of over-directed acts and motivations.

The presumption is still that stories should reassure us, and Defoe dismisses it. Yes, he holds the camera, but he keeps dropping it, because there are so many bodies in the way. Defoe wrote at speed (the book was finished in just over three weeks), and it contains contradictions, though they seem to embrace the predicament described. They’re confusions that belong to panic: there were always enough people to bury the bodies; there were no people left in some streets to bury the bodies; the plague didn’t reach the ships moored in the Thames; then again, it did. HF gives thanks to God, towards the end, when partial abatement brings people back into the light, but the homiletics are designedly unconvincing. Some things are so overwhelming they destroy our fixed beliefs. Surely what the Great Plague finally did, in a busy interconnected early-modern world, was to cremate faith in divine appointment of any sort. It fired up the engine of the Enlightenment. More powerful by far than HF’s thanksgiving is his italicised outburst as the citizens break their quarantine: “the best physic against the plague is to run away from it”. The implied scepticism about divine protection chimes with the author’s own vinegary Dissent but also gives an answer to the question that has bothered the narrator from the start, and which drives the whole story: “Should I stay, or should I go?”

His younger brother leaves London early on, and advises HF to do likewise. HF stays to protect his business and property – he’s a saddler – but trade packs up anyway, and he is left to make shaky memorandums of events, nervous forays across the river, brief appearances as an examiner of infected houses. The film, like the book, ought to be a caravan of episodes, made up of people going through the same horror in different ways. The route it follows circles back to the one central question. Some episodes are no more than quick, terrible visions. Once the houses begin to be shut up and watchmen appointed, the afflicted have no choice but to die where they are. Except that the sound are confined with the sick; torn between love and the love of life, they pre-empt the council men with the bloody paint, daub their own doors with crosses so that they will appear already to have been shut up, and then flee by night. But “whither should they fly”? Many of the afflicted wander abroad in a state of disinhibition, dancing in the streets, kissing strangers, or bringing infection with them to inns of refuge where the maid forgets to attend until the morning, finds a corpse, and then perishes herself.

Two other sequences, assuming the larger proportions of a play within a play, are fully elaborated responses to the governing dilemma. In the first, after two weeks of self-isolation, HF walks to the post-house to deliver a letter to his brother. He goes further, testing the bounds of liberty, and comes at last to the river’s edge, at Blackwall stairs, where he finds a waterman, whose wife and child are both ‘visited’, nearby, in a “very little, low-boarded house”. The waterman makes what money he can from tending to the rich merchants and their families on board the ships at anchor midstream, and rows as far as Greenwich, Woolwich and “farm houses on the Kentish side” to buy eggs and butter for his family. He leaves food and money on a stone at a safe distance from the house, and is waiting, now, as HF finds him, for his wife to emerge. She has a swelling, “and it is broke, and I hope she will recover; but I fear the child will die, but it is the Lord – ”. Good writers know when to rest the pen; actors and directors, when to stop moving. The masterly handling of this scene hasn’t much to do with the disease or the waterman’s plight. It is just the shocking fact of his name, of there being someone to call it, and of our being allowed to hear it, adrift on the tide of anonymising destruction: “At length, after some further talk, the poor woman opened the door and called, ‘Robert, Robert’.”

The second major episode, an unlikely Utopian experiment, or parable, could be extracted from the novel and adapted on its own. It concerns three impoverished but resourceful men – an ex-soldier turned biscuit maker, a lame seaman and sailmaker, and a joiner – and has its dramatic roots in the preceding cataclysm of the Civil War. The skill and cunning of servicemen abandoned by the ship of state are brought back to life. The men leave the city, by circuitous means, avoiding checkpoints, thinking carefully about what they can carry (they are but “three men, one tent, one horse, one gun”) and how to get provisions, when they are met by wary villagers on the outskirts of Walthamstow. By wrapping sticks in rags to look like muskets and building a series of widely-spaced fires in the tall grass, the soldier (John) persuades the villagers that they are a large company and extorts from them plenty of bread and beef. On coming to Epping, the ruse is reversed. This time, John says, far from being a desperate company, they are pious and few. They win over the locals and establish a self-sufficient commune. In a further reversal, the commune is so successful it attracts the Epping villagers themselves, some of whom are already sick with the plague, and so the mirage of sanctuary dissolves.

HF counsels flight, but flight is an illusion, Defoe says, because fear of the stranger cuts both ways – the people offering refuge are strange, too – and safety doesn’t lie at home, either. You can ask questions of the seeming well, but will you be satisfied with the answers, “if the arrow flies unseen, and cannot be discovered”? The position of the citizens is pitiable, insoluble, but not to be wondered at. Their condition is not bleakly illustrative, as it is for the characters in Albert Camus’ La Peste. (Like Defoe, Camus knows that lessons, philosophical or religious, tend to disappear inside the experience of catastrophe, but somehow, at the level of tone, the later writer finds them harder to resist.) Defoe’s victims are subject to the dramatic irony of history, of course: we know, as they do not, how the disease was spread. Most guesses about transmission in the novel are wrong, though not wildly so – carrier “insects” are briefly invoked at one point – and to feel that the characters act mistakenly, when they slaughter thousands of cats, the rats’ natural predators, is to side with superficial narrative resolution. In fact, the book is remarkably open-ended. A film would be free to imagine survivors who were more than lucky – people who sold onions or pepper, or made strong-smelling oils for apothecaries, or who pursued noisy occupations, all rodent deterrents – but it would have to come back to the eyeless zeal of the pathogen itself, from which point of view objective cause and cure are limited by their expression in human beings. Terrible things come to pass, and then pass away. This is a fact. Now: what are we to make of it?

First published in The Times Literary Supplement, May 15, 2020

Pohlmann Baby Grand, c.1935.

Echoes to the Questions of Ethne Alba

The “Quis est Deus?”, or Questions of Ethne Alba, is a medieval Irish lyric, with the calm but pointed, sometimes disconcerting, tone of enquiry – a kind of flinty innocence – characteristic of the early church, and of the ordinary person’s conception of belief at that time, when a deity’s invisibility did not lessen His claim to material reality. For reasons now obscure – I’m a reverend agnostic – the poem made an impression on me in the early 1990s, and I appended a version of its informal title to a suite of solo piano music written in my late teens.

In fact, the suite had its origins as several different pieces of music, some of them for voice and organ, some for solo organ, others for piano. I still have the scores for all of these: some strike me as playable; others I have to imagine in my head, which is what I did when I wrote them. Truthfully, I can’t remember how much was composed at the keyboard and how much on the hoof.

“Echoes” is a recording made at a friend’s house in Bath in 1991 by the producer David Lord. I found the master cassette a few weeks ago, in a box of old programmes, photos and postcards, and had it digitised. As you can hear, I played an old piano (not the one in the photograph, but similar), with slightly off damping. The scores for the various pieces were all laid out in front of me, and I went from one to the next, improvising a little where necessary, but mostly sticking to what I’d written. I don’t know if Ethne Alba would have appreciated them, but here are my answers to his Questions.

“Desert Backbeat”, Chine-collé print, 2011, by John Eaves

“The Lord is Listenin’ to Ya, Hallelujah!” – poetry, Sydney Road, and Carla Bley

If memory serves, I was trying to write a poem about the middle reaches of Sydney Road in the Melbourne suburb of Brunswick, where the shops and butchers and Turkish cafés and semi-abandoned bridal boutiques face each other across a patched and uneven surface clogged with traffic. Trams clatter up and down the street as they have done for more than a hundred years. The late Victorian buildings, many of them, retain their coloured plaster facades, like cake-decorations with pink and brown piping. The more I looked at them, the more they refused to obey what Thom Gunn has powerfully called the “occasions” of poetry, which are not decisions to write so much as a sorting of real and imaginary experience in which one must be alert to the happenstance, the inner prompting that presents itself as a found object or an unexpected idea.

I’d injured my back and was in a fair amount of pain. Helpful distractions included the energy and beauty of my surroundings, the birdlife, the markets, the sounds of flyscreens slamming shut in the wind, the kindness of the people I met, the Polish lady on Lygon Street who took me under her wing, the odd way in which my relocation to Australia had both banished and revived childhood memories, because of course memory is dynamic – a conversation between past and present in which the retrieved event serves the needs of one’s current predicament. Memory is meaning in search of form.

That search is a treacherous thing in both prose and poetry. Too strenuous an attempt to fix the results on the page can produce something aggressively personal or inert – the writer getting in front of the camera or in the way of a more unresolved and therefore interesting image. But if you can slide past a declared aim and speak in an aside, then the “adventures in writing” (Gunn again) can begin. I am taken with the notion of asides: they are, in early modern drama, the formally informal convention whereby people – liars especially – let slip the truth. I write a lot of them. They are part of the flow of a scene or narrative, but relatively unplanned, quickly ushered in. When we find ourselves digressing or speaking in asides, we are often saying what we really think but would be embarrassed to own. There is something Proustian about even the most trivial examples. It is almost as if we can tell the truth only when it doesn’t matter.

This is by way of introduction to a poem I wrote, unusually for me, with few corrections. It is somewhere between an aside and a soliloquy, and there is plenty in it that strikes me now as peculiar – that “helium-filled Titanic”, for instance. But the strain in the image is part of the overall sense of unburdening that came with staring at the shop-fronts on Sydney Road, and the heart of that staring was a revelation of indebtedness. I wanted to tell my father, who loves listening to music, how much his example has meant to me. I listened to music as I walked up and down Sydney Road, and for a while I listened every day to the American jazz composer Carla Bley, whom we both admire. I associate her gospel instrumental, “The Lord Is Listenin’ To Ya, Hallelujah!”, with Dad, with Melbourne, with the smell of meat in Brunswick market, with the dramatic monologues of U. A. Fanthorpe and Billy Collins, with the Psalms of thanksgiving.

The Lord Is Listenin’ To Ya, Hallelujah

for John Eaves

Gary Valente’s on trombone and you’re mixing acrylics.

The sound is that of a lone magisterial goose laying

about itself in cycles of wide-eyed, tearless grief.

The other farm animals stare at it in dismay.

“What’s got into her, apart from extra corn?”

Lately, people have been telling me I should stop

writing about my childhood and move on. Where to,

they do not reveal. And how can I,

when it follows me down Sydney Road,

in even these blue nethermost latitudes,

flapping its weird relic wings in despair

at all my pointless running about?

I could try, I could for once just try

listening, as I do battle with phone companies,

internet cafés and robot ladies grateful for my abuse,

to what the music is saying, however painfully

long the passage of recall might be on the way

back to mornings of hopeless pleasure in a room

filled with light and colour, your paintings

streaming on every side like pennants on a standard

or the tricolor plastic strips at Dewhurst the Butcher.

Perhaps that’s why the goose is so frightened:

though even in the grip of the most plausible terror,

knowing full well what goes on behind the curtain

where the rosy-cheeked lads let fall their arms,

the noise she makes tells a different story.

Instead of trying to sound beautiful, let it blow.

Live as though you were already dead and free

to wander the brazen rooms of this honking solo

which lifts off like a helium-filled Titanic

and floats effortlessly upwards laden with coughs,

barks, distant alarms, cheers, dropped glasses, sleep apnoea,

locked-ward chatter from the audience and every other song

of inadvertent praise you can imagine hailing from the top deck.

S113 “Talking With A Psychoanalyst: Night Sky”, 1975–80. Private Collection. Copyright Estate of Ken Kiff. Photograph by Angelo Plantamura. Used with kind permission.

Ken Kiff – The Sequence

It is very hard to write persuasively for others about the works of art that one loves, unreasonably and irrationally. “I am a Jane Austenite“, said E. M. Forster, “and therefore slightly imbecile about Jane Austen.” In Forster’s case, the childish imbecility perhaps conceals an element of exquisite critical self-satisfaction: ‘I have been inducted into the ways of this writer or artist and I can only feel sorry for those who are too sophisticatedly stupid to feel as I do.’ An actual child would see things differently, without apology, and it is the work of a lifetime for many poets and artists to think their way back into that state of mind which encounters the world, and consciously ferments the encounter into a response, for the first time. It is Wordsworth’s subject, of course: the deep love of being that trumps learning, as learned as he might be. He’s sceptical about it, which is interesting, perhaps because he knows that this “under-sense” of replete identity with something (usually nature) is apt to sound pretentious, or even like a disavowal of adult responsibility. He calls it an “overlove of freedom” in Book VI of The Prelude. At the same time, it is indubitably real and important to him, because it represents the mystery of artistic immersion, which he experiences as a “treacherous sanction” of the critical. Better than any explanation, and worse, because it is not to be trusted.

The work of the English painter Ken Kiff (1935–2001) confronts this head-on: his is a riotous, protean imaginary of sexual archetypes, Shadows, surreal encounter, landscapes and artistic anxiety that takes seriously (though not sombrely) the whole business of love, the personal, sharing beyond words, and how hard it is to give a reliable account of these things to others. The open-ended summation of his, on the face of it, very un-English, wrestling with the Psyche, and with Jung (Kiff was in analysis for some years), is a 200-image serpent of continual making called “The Sequence”. He began it in 1971 at the age of thirty-five. A beautiful sketch, with an Uccello-ish dragon bottom left, and a tree dividing the page like a pale green fuse, was left unfinished at his death at the age of sixty-one. The paintings are mostly acrylic and pastel on stretched paper, with the gummed tape around the edges preserved as a reminder of their essential provisionality. Walking round the astonishing exhibition of sixty or so paintings, at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich, is like visiting Regent’s Park Zoo with something from the reptile house as your anima and guide – a salamander, say. Kiff likes salamanders. Symbolic and actual, clearly emanating and signifying from inside the head, but smooth and scaly to the touch – a highly proprioceptive fantasy.

There is nothing like these paintings anywhere else. They do not belong to the main outgrowths of European Surrealism, with its manifesto-led disaggregation of narrative elements, its collage and taboo. They are not Abstract, although two abstract geometrical forms – a blue spike, like a tooth, and a flying parallelogram, like the Phantom Zone from the Superman comics – find their way into compositions otherwise made up of anthropomorphised animals, floating heads, defecating or spitting bodies, lovers, smiling naked figures, and darkly observing or listening shapes who might be the painter or his analyst. They don’t seem aware of their own facility, which is the problem with Chagall, and even Dali, whose idea of the unconscious was heavily branded from the start. They’re not faux-naive, either, or archly primitivist, in that way you can’t help laughing at when artists find a shtick and can’t stop waving it (Hodgkin’s frames). They’re not unaware of the rest of art – far from it – or trying to be singular. In “Spitting Man” (1976–80), a seated thick-set figure, pink and monumental, expectorates other smaller figures. The heaving up is a reverse-engineering of Goya’s famous Black Painting, “Saturn Devouring His Son”, and like that image, which started out as a wall painting, Kiff’s fleshy acrylic has an air of the built about it – of plaster and blank, wall-eyed permissions. They are happy to refer to things. In “Talking with a Psychoanalyst: night sky” (1975–80), a tremendous dramatisation of the scene of analysis, but in a real room with proper curtains, the two breast-like hills outside the window are Uccello again – the Fiesole hills in Florence.

But, in referring to things, to ideas and other artists, to writers (there is an astonishing drawing of Mayakovsky blowing his brains out), to himself, Kiff never feels as if he is drawing on a store of decided knowledge or material that has been imported from another discussion or medium. What comes up for him in the process of painting is the unaffected recreation of passion and erotic delight, the importance of colour as a ground to which every other question of formal invention and planning is subject, and in both the passionate and colouristic manoeuvres he is convincingly childlike, without being creepy. The paintings resemble those semi-ritualistic, incrementally developmental games that children play as they discover for the first time, and with a never-to-be-recaptured combination of hesitancy and sweeping confidence, their relationship to the external. That’s why the donkey’s legs (“Donkey”, 1976) are so accurately seen, the soft kink of the hind legs, and the scale of the animal so intuitively grasped before a mark is made. That, too, is why the sun is smiling. It’s not kitsch. It’s a matter of stepping truthfully into the moment. The world exists before my eyes, and I am making it.

Idealism agrees, and so would C. G. Jung. For the great symbolist analyst, the psyche was individual and irreducible to anything else. This is also broadly the position of philosophers like Thomas Nagel and John Searle, for whom the mind is physical but not in ways we currently understand; for whom the subjective viewpoint, our looking-on at the world, is not a skim on the surface of objective reality but a puzzling part of it. And inextricable from it: this may be the most important point to consider, Kiff suggests. Before we recruit him to one side of the subjectivist debate or another, we need to remember that he is an artist and a maker before he is anything else, and that artists do not feel they are transcribing or representing or interpreting the world. They’re just in it, and they’re in it more comprehensively for their willingness to have an experience that doesn’t try to isolate the understanding. The problem with the language of symbols in artistic activity – the sun is the mother principle, the shadow challenges the ego, the tree recalls Ygdrassil, and so on – is that the attribution of meaning takes place after the event, when one is only looking on or looking back. One wants to ask: how can unconscious meaning survive into consciousness? Here is the logical obstacle in the path of psychoanalysis. To get at meaning, we need to relive, not describe, and experiencing art, Kiff thinks, is one way of achieving this.

We want the kind of absorption in all our contemplative activity that neither stiffens into description nor threatens a psychotic episode in which objective distinctions disappear (Wordsworth’s “treacherous sanction”). Kiff puts it best himself in a long and sensitive letter to his friend, the writer Ian Biggs, dated June 10, 1998: “My position is to emphasize that the unknown is the unknown. That the unconscious is unconscious. ‘Self’ is an unknown, as ‘wholeness’ is an unknown . . . Painting evokes the sense-data by which we read the world, I suppose . . . It is an independent thing, however, because it isn’t the servant of our conscious activities, nor is it merely a product of our unconscious activities, nor is it a mirror. It is a highly developed medium with a continuous logic.” In other words, painting isn’t a record; it’s a form of pattern-forming attentiveness, in which things that are seen change as the painter looks at them, and in a way that feels logical and sensible, however unlikely the changes. It’s striking, as one moves from painting to painting, how genially unperturbed Kiff’s dramatic personae seem to be by all the psychic chaos. Nothing puts them off their stroke; there is illness and fear (a man throws up), but there is also comfort (another man, rising out of the ground, comforts him). Domestic routines are done naked. It’s Eden, or the 1970s, or a bit of both, maybe.

In “Posting A Letter” (1971–2), a beaming male nude strides towards a smiling red post box with an envelope in his hand. He is lifted up above the ground, above his own shadow; he walks on air. Behind him, to the left of the sheet, a bowler-hatted commuter disappears behind a tree. Both figures are regarded with total self-possession by an ant-eater, where one might possibly have expected a dog or a squirrel. The surprise is like the bend in a pencil when you put it in water and the memory of the first time you looked at that phenomenon. It is a real thing, an image, and a piercing emotion all at once. Emma Hill’s excellent catalogue to this rejuvenating show – the most enjoyable I have seen, anywhere, in years – reproduces an email from Kiff’s former student Emma Bosch, who remembers him at work on this particular painting. Kiff was a great correspondent, and he talked, Bosch says, about “the excitement of leaving a letter in the postbox and then waiting for the reply.” Hope is often an unreasonable and irrational feeling, of course, but it’s sentimental to think it always without foundation. The man in the air could fall. At the same time, he is buoyed up, right now, by sheer communicative delight.

First published in Brixton Review of Books Issue 5, March 2019

Dulwich Woods, London, looking down towards Lordship Lane, SE21

Beginnings

The sellers pull up at the gate from around 9am, every Saturday and Sunday, and the buyers are already there, in packs. Drive in too slowly and your car will be mobbed. People bang on the windows anyway, yelling “Watches? Any watches? Jewellery? Any clothes?”. It’s mudlarking crossed with Mad Max, the engines gunning, Tina Turner’s “Simply The Best” curdling the air, huge men wandering around with burgers and plastic bags full of, well, crap. And tools.

Why are there so many tools, in among the discarded children’s toys and damp-fattened books and boxes of armless sunglasses and remote controls for screens so remote they no longer exist and terrifyingly stained overalls? A part of the answer must be that car-boot sales have an obvious kinship with travellers and the idea of trade as a way of handing on useful skills; with ironmongery and agriculture. Here are boxes of files, knives, spanners, pitchforks, angle-grinders, claw-hammers, rotavators and chisels. These heavy goods are by no means the only desirable objects. Everything goes. “This is insane”, says my friend Stuart, who has a car-full of stuff from his garage to offload.

The woman next to us, on the touchline, is cross because someone has nicked her shoes. She looks round, outraged. “You, thief!” she says, pointing at a young girl with a pram. “I never”, the girl replies. Someone reminds the woman that the shoes weren’t nicked: she sold them a minute ago and has forgotten. “Oh.” The young mother rolls her eyes, pushes on and stops at our mat. “How much for the lamp?” It’s an orange metal standard lamp, with a fitting hanging out. “Five quid. It’s vintage”, says Stuart. His honesty gets the better of him: “It needs rewiring.” The girl nods, unperturbed. “My boyfriend’s an electrician, but I’m on a budget.” She smiles. She comes back later. Four quid is still too much, and so, later still, is three.

Euphemisms for “broken” are part of the sale’s inventive dialect. “It’s still in its box” (because it doesn’t work) is a popular one. Along with “They’re Adidas / Nike” (with the tread worn away) and the occasional bespoke understatement. My first typewriter, which I loved, was a Silver Reed Silverette. In Fisher Athletic FC’s goalmouth, a part-time psychic – I know this because she has a card – is selling an identical model and I’m tempted to buy it. The carriage goes one way; the release catch won’t release. The back of the typewriter is staved in. It has been hit or bashed with a tool, or perhaps thrown across a room. Maybe the psychic knows. “What happened, here?”, I ask. But she’s having none of it. “You can write nicely with that”, she says, flatly. “It’s just . . . unclipped.”

The whole place is unclipped. It’s not the objects so much as the silent relationships between them and their sellers that gets me going. When Stuart invited me along, I thought “Great! Material!”, as you do if, like me, you’re pondering a new story. Not that I expect to be writing a novel set in SE16 about a car boot sale; but I do expect to overhear suggestive remarks and glimpse predicaments. The mats and trestle-tables are laden with the no-longer wanted – an attractive idea in itself and one which raises the question “Why?” or “Who says?”. As I walk away from the woman with the typewriter, I turn a “different quality of attention “ (Hilary Mantel’s guarded phrase) on the chaos of the sale, and find myself considering not simply what is being said or done, but how the adrenaline and suspicion driving it might animate a trial, a fight, an opening scene. Paying this kind of attention is important, and rather heartless. It is a form of staring, and I’m not sure I approve of it.

The buyers are poor. When they knock on the car window, shouting “have you got any clothes?”, it’s because they need clothes, not because they’re some sort of scenic metaphor for the end of the world. Who do I think I am, wandering about looking for the links between things? What kind of twisted self-indulgence is that? Feeling good about feeling this bad, I’m suddenly free to spot a dartboard next to an unrolled sight-test, with its big letters dwindling to small ant-like characters, and a man sitting alongside both with several sets of spare legs – not prostheses, but the legs of display dummies. I can’t quite piece this lot back together. He’s also selling some tubs of aqueous cream and a book: Dancing in the Light, “another” #1 memoir by Shirley MacLaine.

Perhaps these things aren’t connected and there isn’t a story. Stuart has brought along two golf-clubs, which don’t belong to him. They are the casual bequests of his flat’s previous owner. Of course, some stories do appear to suggest themselves, like objects at a sale. Daphne du Maurier’s “The Birds” “began” after the author saw a flock of seagulls circling, menacing, a farmer in his field. Anna Karenina “began” with a newspaper clipping about a suicide. Most are not startled into life, however; their authors may see or overhear things, but those things await a context, which tends not to be a product of excited invention but of patient stitching-together.

It is an uncertain, dreamlike process, starting a novel, and one which, like the sale, has no official beginning. I know that what I’m waiting for is an emotion from the past, echoed in the present. A moment of joy or bewilderment, and exposure, often allied to feelings of culpability: What have I done? What will I do next? How can I put it all right? I’m not particularly interested in the origins of that feeling. What I care about is the quality of the emotion, its electrical sensation as I make the memory circuits come alive. When that happens, I might be on to something.

The craziness of the sale recedes, like a swift tide. People and objects disperse. Tina Turner is on the Jubilee Line back to Nutbush. Before it is quite over, the girl with the baby, who eventually bought the orange standard lamp for £2, taps me on the shoulder as I’m packing up. “That lamp is f***ed. My boyfriend can’t do anything with it”, she says, and for a second I’m speechless with remorse. It isn’t even my lamp. Stuart has made himself scarce: so much for his honesty. I manage a kind of cough, and dig into my pockets for a refund. She laughs – and she’s gone. With the pram and no boyfriend that I can see. I feel apologetic, with no one to apologise to.

When I was about six I fought with my brother in the kitchen and we broke a Mexican dish. My father is an even-tempered man, but on this occasion he went beserk – eyes popping, spittle flying, the works. I never found out why. Was it valuable? Perhaps – in more ways than one. What came back to me was how sorry I felt. And now I’m left with this feeling, in a new setting, about broken things and the effort of others’ lives: what they can’t say, because they’re protecting you, because it runs too deep or because the gulf between you is too wide. Fisher Athletic FC, “The Fish”, was wound up in 2009. Supporters formed a new football club, Fisher FC, which still plays in Dulwich. The old grounds hold a car-boot sale and ragwort curls in from all four corners at once. Over the water is Canary Wharf, which looks unbreakable, but isn’t.

First published in the Times Literary Supplement, 2012